Researched and written by Derin Bray

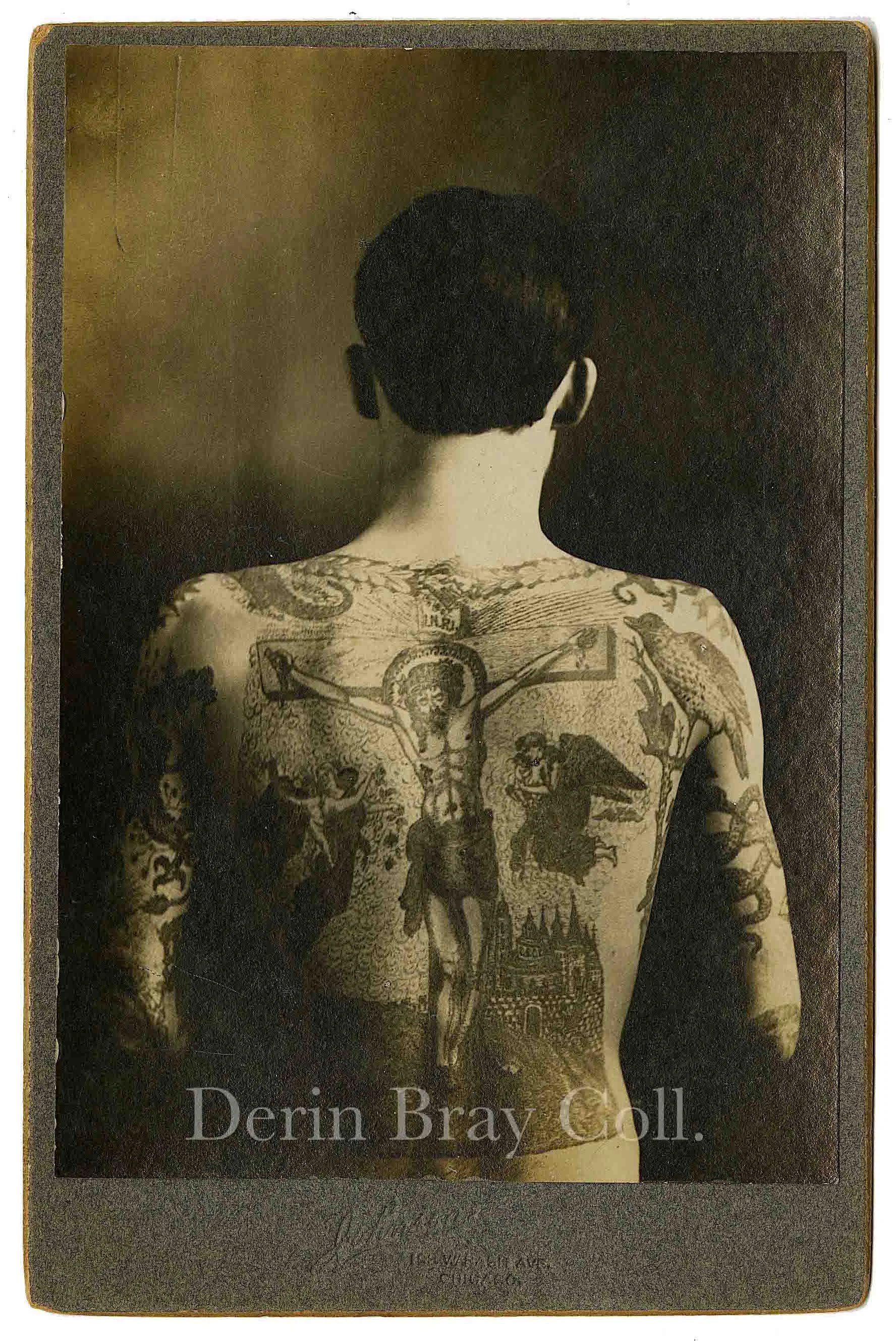

Joseph Bernard Harkin, aka Barney Kruntz, Cabinet Card by J. S. Johnson, Johnson’s photo studio, 193 Wabash Ave., Chicago, IL, ca. 1905. Derin Bray Collection

Before transforming himself into a tattooed marvel, Joseph “Barney” Harkin was better known as a plucky young tailor from Toronto, Canada. And like many performers who climbed to the top of their profession, his life story reads like a work of sensational fiction, replete with magicians, train wrecks, and even the mummified body of John Wilkes Booth –or so he claimed!

Joseph and Agnes Harkin. Private Collection

By the time he was eighteen years old, Joseph “Barney” Harkin (1883-1943) had already set his sights on a career in show business. He moved to Chicago around 1902 and quickly found himself on South State Street, one of the country’s busiest and bawdiest entertainment districts. While there he became acquainted with old-time tattooer and tattooed attraction Albert “Dutch” Herman, aka “New York Dutch.” The exact circumstances of their meeting are unknown, but Herman would soon hand-poke hundreds of designs on Harkin’s body, including an elaborate backpiece depicting the Crucifixion of Jesus.

Joseph Harkin, aka Barney Kruntz, with Campbell Bros. Circus, 1909, by Frank Carney. Courtesy of Circus World Museum

For the next fifteen years Harkin exhibited himself –sometimes as Professor Barney Kruntz— at Chicago dime museums and with sideshows that crisscrossed the country, notably Sells-Floto, Al. G. Barnes and Barnum & Bailey. His wife Agnes (1884-1974) joined in too. She performed a popular “Den of Snakes” act, often under the stage name Viola.

The London Dime Museum, Chicago, ca. 1907. Barney Harkin performed here in 1903.

Barney Harkin, Tattooed Man, exhibited himself at the London Dime Museum in Chicago. New York Clipper, April 18, 1903. Albert Herman was also a frequent exhibitor at the London Dime Museum.

Like many illustrated men and women, Harkin padded his income by tattooing. He even dabbled in the supply business. Throughout 1909, he and his father-in-law, James Black, advertised tattoo machines, design books, and inks from their home base in Chicago. Black, a former worker at a forge in Toronto, may have brought his metalworking skills to bear on the craft-side of the operation.

Harkin & Black Advertisement for Tattoo Machines and Supplies, 200 S. Halsted, Chicago, IL, Billboard, Apr. 10, 1909.

Hagenbeck-Wallace was the last circus the Harkins traveled with as performers, and for good reason. Life on the road was grueling, especially with young children. And travel could be quite dangerous. On June 22, 1918 near Hammond, Indiana, an empty train piloted by a sleeping engineer plowed into the idle train carrying Hagenbeck-Wallace’s 400 performers and personnel. It was one of the deadliest crashes in U.S. history. Barney was aboard the vehicle. He managed to walkaway from the crash, but many weren’t so fortunate —86 people died and more than 127 were injured (learn more about it here).

Aftermath of the Hagenbeck-Wallace train wreck near Hammond, Indiana, 1918. Courtesy of the Hammond Public Library

The wreck undoubtedly shook the Harkins. Whether it motivated their next move is unclear, but they retired their acts the following year and purchased an arcade on South State Street. Evidently business was good. By 1921 Barney had pulled together enough money to purchase one of two theaters owned by famed magician Howard Thurston. Located just a few blocks away at 518 South State Street, the Trocadero, as it would become known, offered burlesque shows on the first floor and a museum of oddities on the second.

Billboard, October 29, 1921

But the theater business presented its own set of challenges. Local reform organizations determined to run Harkins out of town for promoting immoral exhibitions. As one investigator reported, for a mere nickel, lewd girly shows could be watched through a peep hole. The police and health department followed up on such tips with raids, often arresting some of the women and their male customers. Harkin himself was hauled away on a few occasions. Things quickly came to a head in the the spring of 1923. The state attorney general filed a bill for injunction against the veteran showman, alleging that the Trocadero was operating as a brothel “in which women solicit patronage and…obscene performances are staged.”

Not surprisingly, Harkin made a swift break from the museum and theater business. And before long he was back on the road —this time traveling by truck— with a minstrel show and later a war exhibit that boasted a vast display of ancient military artifacts. During an especially memorable appearance with the S. W. Brundage Carnival in 1924, chaos broke out in Harkin’s tent:

The monkey speedway was spotted next to Barney’s war show, and one of the simian daredevils escaped, and got in among the war relics. When finally caught, he was reported attired in German, French, and Irish military paraphernalia. But Barney, so front-line reports stated, retrieved his w. k. Scotch pea cap.

At the outset of the 1930 season, the Harkins interrupted their engagement with Brundage show to seize a rare opportunity. Barney had been in the market for a flashy new attraction and found just thing on a potato farm in Declo, Idaho: “The real embalmed body of John Wilkes Booth.”

Advertisement for the embalmed body of John Wilkes Booth, Billboard, May 10. 1930.

Indeed, for more than two decades the leathery remains of a man known as John St. Helen (aka David E. George) had been exhibited throughout the country as the body of John Wilkes Booth, notorious assassin of President Abraham Lincoln (read more about it here and here). As the story goes, St. Helen had confessed his identity to his lawyer, Finis L. Bates, who later promoted the conspiracy through the popular book The Escape and Suicide of John Wilkes Booth (1907). Shortly after he came into possession of the corpse, Bates began leasing it to showmen, who added to the spurious story with affidavits and medical examinations. Interestingly, reports substantiating the claim never mention whether the mummy featured the tattooed initials “J. W. B.,” which Booth had crudely pricked on the back of his hand as a boy.

The Harkins purchased the controversial attraction for a purported $5,000 and toured with it throughout the 1930s. A spread in Life magazine captured the exhibit in its full glory. Barney can be seen collecting the 25 cent admission, while Agnes provides the crowd with x-rays intended to corroborate the story of Booth’s escape and his subsequent life on the run. Behind the podium painted sign boldly declares “$1,000 reward if proven not genuine.”

“Twenty-five cents admission is charged to see the mummy. ‘Barney’ Harkin tends gate. His wife does the explaining,” LIFE, July 11, 1938. William Vandivert—The LIFE Picture Collection/Getty Images

“An X-ray of mummy’s stomach, exhibited by Mrs. Harkin, shows signet ring with “B,” supposedly swallowed by Booth,” LIFE, July 11, 1938. William Vandivert—The LIFE Picture Collection/Getty Images

Barney and Agnes Harkin were true show people. By virtue of grit, talent, and force of personality, they blazed their own trail through the rough-and-tumble world of sideshows, arcades, dime museums, and carnivals in early twenty-century America. Barney passed away in 1943 at the age of 60. Agnes continued to live in Chicago until her death thirty years later. They are buried in Acacia Park Cemetery in Chicago.

Obituary for Joseph Bernard Harkin, Arlington Heights Herald, December 31, 1943.

Notes:

1. Citations for this article are available upon request.

2. Joseph Harkin was born in Duluth, Minnesota, but moved to Toronto at an early age. He was working in Toronto in 1901, moved to Chicago at an unknown date, and returned to Toronto in 1902 to marry Agnes Black.

3. It’s possible that Harkin had existing ties to the amusement world. His father-in-law, James Black, was described as a veteran showman in his 1922 obituary in Billboard magazine. At the very least Black played an important role Harkin’s career. He partnered with him in a tattoo supply business in 1909 and later sold tickets, most likely at Harkin’s arcade.

4. Harkin’s old friend, Albert “Dutch” Herman, aka “New York Dutch,” may have worked in the museum. By 1925, after Harkin had exited the museum business, Hermann set-up shop at Thurston’s other dime museum at 526 South State Street.